(Above: Samsung Galaxy Ring)

Oura might have rattled their saber a bit too vibrantly, and a bit too pre-maturely, at the wrong entity. In doing so they’ve upset a company not afraid to wield its massive army of lawyers, causing Samsung to preemptively sue Oura, maker of the Oura smart rings. And if you’ve got in 15 hours of flying as I did this week, then the 32-page legal filing makes for some fun legal spaghetti to untangle.

As you may remember, earlier this year Samsung announced their intentions to make a smart ring, the Galaxy Ring. At launch, very little detail was provided (basically none). Nonetheless, within hours of the announcement, Oura immediately started a public press offense against Samsung. Oura’s CEO and press team focused almost entirely on Oura’s intellectual property (read: patents).

In fact, Oura even reached out to me just a couple hours later, providing CEO quotes, and offers to talk to their executive team – almost all of which were about their patents and IP. In fact nothing in those initial communications from Oura discussed their technologies, or any technical competitive advantages. Instead, it was all about patents. While it might have been Oura’s intent to use Samsung’s entry into the smart ring market as a marketing exercise, it now appears Samsung was displeased by the affront.

Now it’s notable that not all patents Oura has are actually from Oura. In fact, a number of the patents were scooped up by Oura via the acquisition of patent portfolios. In the filing, Samsung details how a number of patents were initially created by San Francisco-based Motiv (of the Motive Ring). In 2020 those patents were acquired by Proxy, Inc. Followed by Oura’s acquisition of Proxy in 2023.

Innovator or Patent Troll?

(Above: The Oura Ring)

The lawsuit is wide-ranging, but starts off with setting the stage that Samsung is concerned with Oura’s increasing lawsuit activity against upcoming competitors in the smart ring space. Samsung says:

“Oura has seen fit to assert infringement of its patents based on features common to virtually all smart rings, such as the inclusion of sensors, electronics, and batteries, and displaying a summary of the sensors’ measurements to the user, often in the form of a “score.” And Oura has sued at least one manufacturer of a competing smart ring product even before that product was delivered to customers in the United States.”

Samsung noted that after the January 17th, 2024 announcement of the Galaxy Ring, they received FCC certification back on March 28th (2024), followed by the finalization of the design in May. They’ll start production in the next few weeks, and then expect to “begin sales and shipments” this August. The document also details more about the sensors in the ring, as well as various use cases. In a nutshell, the Galaxy Ring seemingly provides more or less the same activity/sleep/HRV/blood oxygen/energy/recovery type scores as most other wearables on the market today.

But Samsung is specifically concerned about Oura trying to impede the launch of the Galaxy Ring via a potential lawsuit (logical given Oura’s statements). Thus Samsung deciding to sue first is effectively a blocking maneuver to outline how they aren’t stepping on any of Oura’s patents, while concurrently outlining areas that they believe are questionable in Oura’s patents.

Samsung starts by invoking the ‘Good Samaritan’ angle on behalf of all smart ring companies, essentially saying Oura is a patent troll, noting in the filing:

“Oura’s pattern of indiscriminate assertion of patent infringement against any and all competitors in the smart ring market, and its statements confirming its intentions to assert its patents against all competitors in the market.”

It continues:

“Each and every time a major competitor has developed and/or released a product that competes in the smart ring market, Oura has filed a patent infringement action against that competitor.”

From there, the document highlights, sequentially, each of the cases Oura has made it an annual tradition to file patent lawsuits against smart ring competitors:

Oura’s lawsuit against Circular (May 2022)

Oura’s lawsuit against Ultrahuman (September 2023)

Oura’s lawsuit against RingConn (March 2024)

I mean, I’m rarely one to agree with anything Samsung does technically in the sports technology and heart rate/sleep fields. But, their point is valid here.

Now, in not exactly the same words, Samsung is basically calling Oura a patent troll. And, depending on one’s definition of a patent troll, that’s probably true. Generally speaking, when the public refers to the term “patent troll”, there are two rough definitions that come to mind:

A) The first is when an established company and patent holder, selling established products will sue other entrants/companies for infringing on their property, usually somewhat excessively, rather than attempting to compete on merit/technology/etc.

B) The second type, and arguably the more correct definition, is when a patent holder (but not a company actually making a competing product) sues with the singular/sole intention to get licensing fees, but has no plans to use the patent themselves. These are typically companies that buy portfolios of patents, merely to sue other companies.

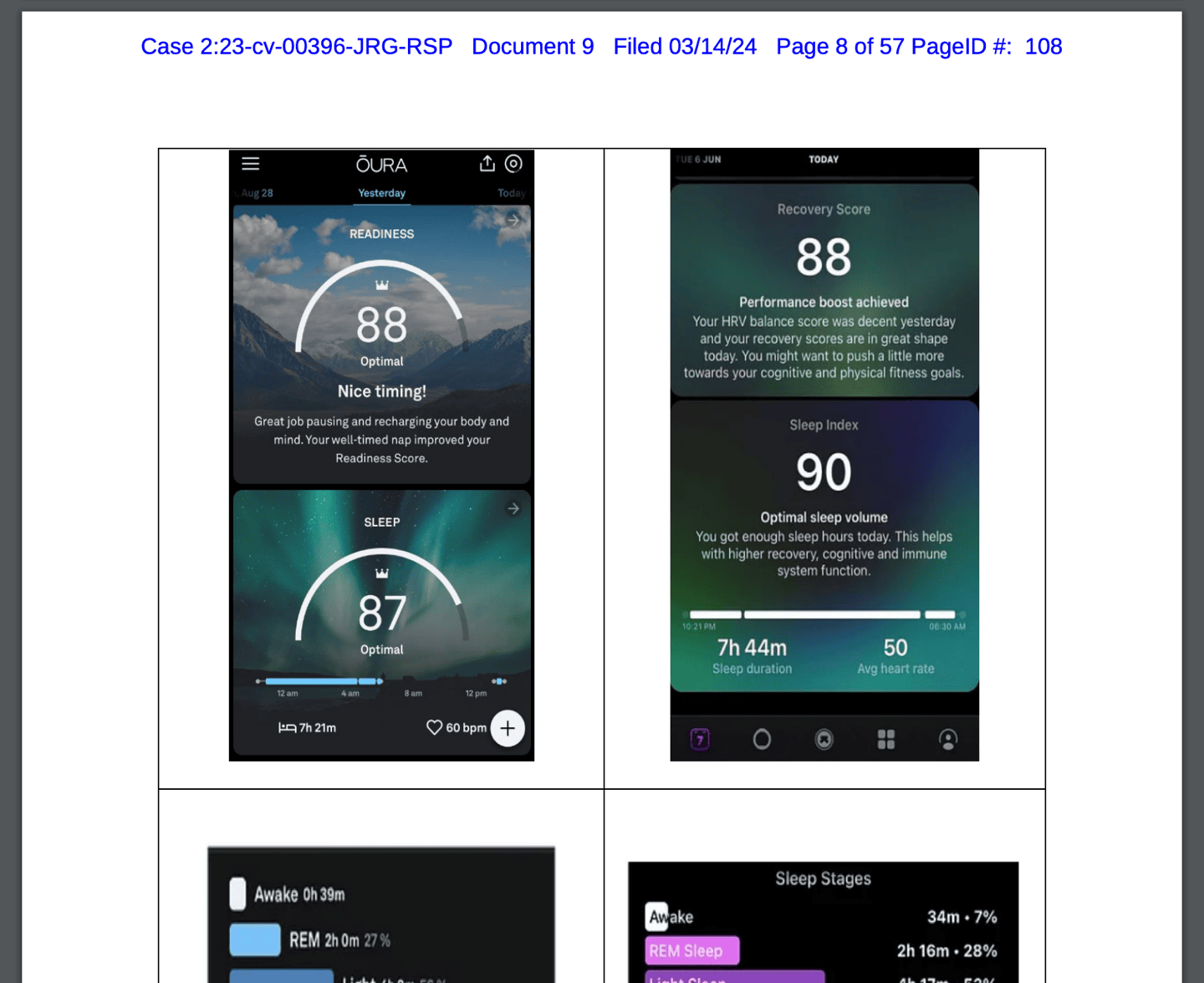

In this case, Oura largely falls under the first category. To Oura’s credit, they make a good product and actively have been selling that product for years. And to Oura’s further benefit, there have been some pretty darn questionable copycats, such as Ultrahuman – who completely and blatantly ripped off every element of their app and more, mirroring Oura. In Oura’s suit, we can see an example of this in the lawsuit (and that document lists a boatload of these examples):

Frankly, as it relates to this software/etc example. I actually don’t have a problem with Oura suing them. They kinda (read: totally) deserved it. That said, from a pure legal standpoint, app design largely isn’t covered by their patents, so mostly the above imagery is busywork to set the stage for the real patient aspects Oura is upset about.

The Patents in Question:

Now, what Samsung cares about here is preemptively getting confirmation that they don’t run afoul of key Oura ring patents. Five specific patents to be exact, out of the more than 100 patents that Oura has. The key patents being discussed are as follows:

1) U.S. Patent No. 10,842,429 (the “’429 Patent”) is entitled “Method and System for Assessing a Readiness Score of a User”

2) U.S. Patent No. 11,868,178 (the “’178 Patent”) is entitled “Wearable Computing Device”

3) U.S. Patent No. 11,868,179 (the “’179 Patent”) is entitled “Wearable Computing Device”

4) U.S. Patent No. 10,893,833 (the “’833 Patent”) is entitled “Wearable Electronic Device and Method for Manufacturing Thereof”

5) U.S. Patent No. 11,599,147 (the “’147 Patent”) is entitled “Wearable Computing Device”

These are the same key patents that Oura has previously used in lawsuits against other competitors. So, while Oura has many patents, these are the core ones that matter, and ultimately the main castle gate to their patent fortress, especially the hardware ones.

The patents in question are basically divided up into two categories:

A) Hardware ones: Related to how you pack electronics into a ring format

B) Software ones: Related to software algorithms, mostly focused on recovery/readiness as it relates to activity

Within the hardware section, Samsung is attempting to assert that its device does not infringe upon Oura’s patents. But that’s somewhat of a guise to then (likely) demonstrate that these patents shouldn’t have been issued. Still, the lawsuit is largely in factual mode, so we see Samsung iterate through each of the patent claims, specifying they don’t meet the claims of the patent. Keeping in mind that a given patent has numerous “claims”, which can be considered like a list of ‘requirements’ as to whether or not an entity is infringing on that patent:

That said, in reading through it, it’s a wee bit hard to see how Samsung isn’t hitting some of these claims, since they are incredibly broad (e.g. inner/outer casing ones). Samsung notes at one point that it’s concerned about how broad some of these claims are, such as one patent that basically says any ring with electronic parts is covered by Oura. They note “in asserting the ’833 Patent against Circular and Ultrahuman, Oura alleges infringement based on a ring containing electronic parts.”

Which again, is setting the stage for Samsung to say the patent should be invalidated.

As we saw in the Wahoo case with Zwift, there are plenty of cases (many in fact) when patents are being issued that really shouldn’t. In that case, the judge questioned many times the validity of some components of the patents, which likely nudged Wahoo towards settling with Zwift, versus risking those patents being invalidated.

In this case, though, I don’t expect to see Samsung settle anything. They’ve got a gazillion lawyers with nothing better to do but research old dcrainmaker.com posts (you’d be surprised how often my older posts get included in legal dockets, due to demonstrating “prior art” concepts that existed long ago – including in the Zwift/Wahoo case).

Oura probably played with fire a bit too early (literally, within an hour of Samsung’s announcement), and as a result, they’re gonna get burned. Even if they somehow win every aspect of the legal case (they won’t), it’ll still likely cost them a massive amount of money and distraction. Sometimes it’s better to fight on product merits, than in a courtroom.

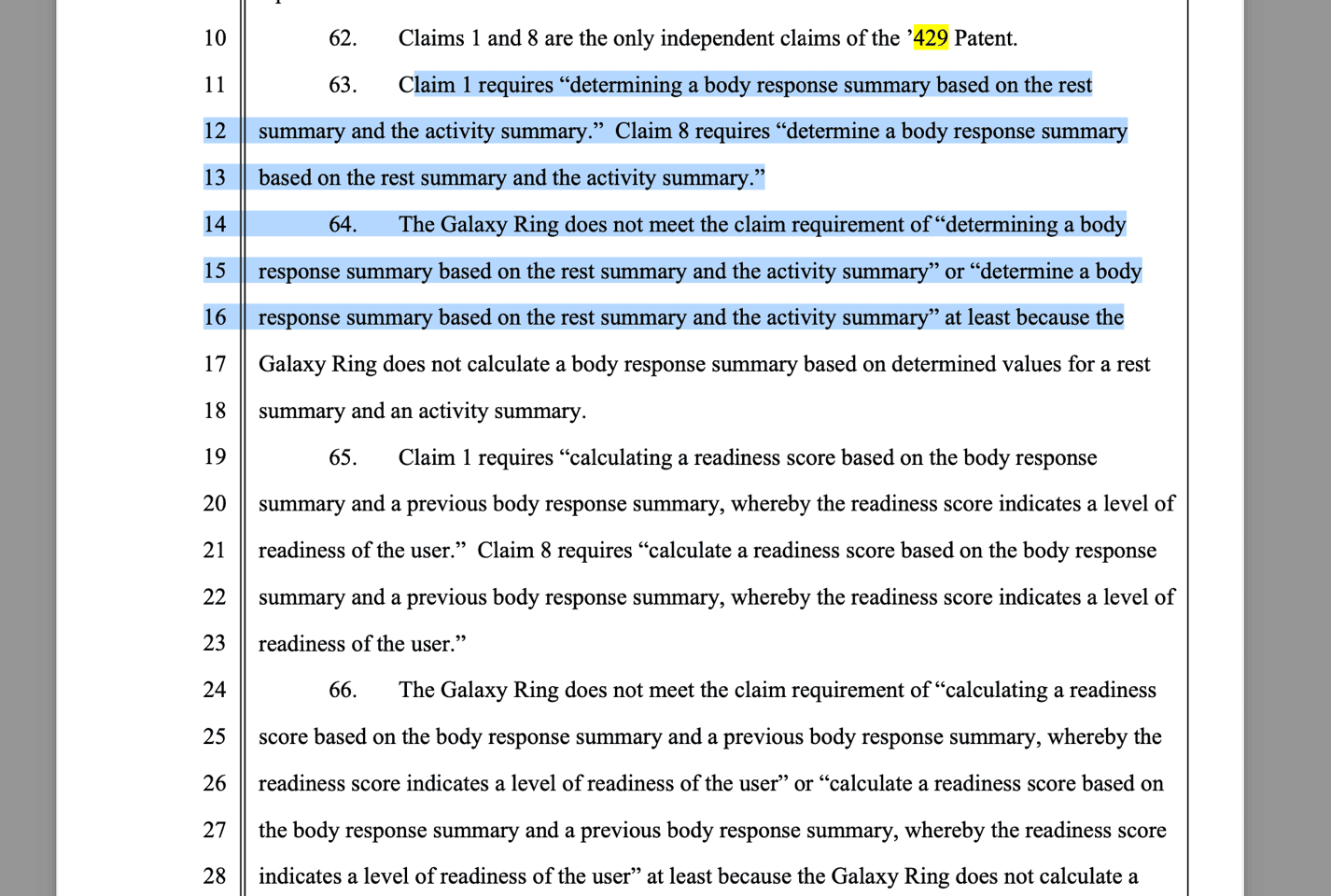

What’s interesting about the existing 2016-era patent by Oura on the software front, is their “Readiness” score (the ‘429 patent). That patent basically talks about taking various inputs (e.g., heart rate, activity, sleep), and then spitting out a score on how it relates to your readiness to take on additional efforts/activity.

That patent essentially boils down to taking those inputs, but specifically from “a smart ring”, and then combining it with algorithms. However, said recovery-type algorithms have been around long-before the smart ring concept. We’ve seen those from numerous players over the years including Garmin, Firstbeat, Polar, Suunto, and others of the pre-2016 era. None of that is new, but adding data coming “from a smart ring is”, supposedly, “new” enough to have been granted a patent for “readiness score”.

Except, when Oura sued Ultrahuman for their “Recovery Score”, it was explicitly because the data came from a smart ring. In this case, Samsung is specifically concerned about their own “Energy Score”, which they say is based on sleep, activity, heart rate, and heart rate variability. That’s also the same as Whoop, Garmin, Fitbit, and others do for their own ‘readiness’ type scores. But again, Garmin/Whoop/Fitbit aren’t in trouble here with Oura, because the data comes from a watch, and not a ring. This is why Samsung is concerned, saying “in asserting the ’833 Patent against Circular and Ultrahuman, Oura alleges infringement based on a ring containing electronic parts.”

But in Samsung’s case, they have to get even more into the weeds. Check out this section here, where they split hairs on how the Samsung readiness score is calculated, versus the Oura one:

Of course, this is all just the beginning. As noted earlier, this early filing is all about Samsung getting in the first shot, in a favorable district, to ensure their initial sales and shipments can proceed without Oura holding things up.

But the longer term goal for Samsung is unquestionably to get some portion of these patents invalidated.

My bet? They’re gonna win. Not just because they have the biggest lawyers, but because some of the existing patents were either too broad, or already had shaky foundations of not passing the obvious test, especially around things like the readiness/recovery score (with the only ‘unique’ angle there being that the data came from a ring).

In talking to a few different industry people this week about it, everyone is of the same opinion: Oura is going to lose the war (even though they’ll win a few battles), they’ll likely get a slate of their patents invalidated, which will then open up the floodgates for other smart ring manufacturers.

Of course, only time will tell.

Thanks for reading

FOUND THIS POST USEFUL? SUPPORT THE SITE!

Hopefully, you found this post useful. The website is really a labor of love, so please consider becoming a DC RAINMAKER Supporter. This gets you an ad-free experience, and access to our (mostly) bi-monthly behind-the-scenes video series of “Shed Talkin’”.

Support DCRainMaker - Shop on Amazon

Otherwise, perhaps consider using the below link if shopping on Amazon. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. It doesn’t cost you anything extra, but your purchases help support this website a lot. It could simply be buying toilet paper, or this pizza oven we use and love.

I’ve been looking forward to your insight since the news first broke of this preemptive lawsuit. Just taking the 10,000 foot approach, if there are GPS smart watches from multiple manufacturers, you would also expect smart rings from multiple manufacturers. The fact that nobody has been able to bypass the Oura’s patents seems to indicate that they are overly broad. The form factor itself seems like it should not be patentable – perhaps the way specific technology has been implemented within the watch is, but that shouldn’t be enough to prevent other players from coming to market.

I can appreciate Oura wanting to protect it’s IP, but there is a balancing act between protecting your innovation and literally cornering an entire market segment.

The best that Oura can hope for is a low-ball settlement from Samsung for licensing all patents. The pricing of this can be cheaper than the cost to Samsung of future legal work and allow Oura to avoid being steam rolled by a bigger pocketed legal team. The advantage to Samsung would be that it would also limit future competitors or at least create a barrier for entry that cheap ring manufacturers won’t want to hurdle over (or risk limboing under), knowing that Oura will continue to fight the good fight on behalf of the patents leaving Samsung unchallenged.

Better one competitor in Oura (who will be subservient to them in the future) than a wave of competitors impacting the customer perception of pricing for smart rings.

Oura obviously needs to pay to PatentTrollfromtheBushera.com, which patented using a computer to engage in using a computer to file patents in a manner that goes back to Sybaris.

Thanks and as usual excellent research and commentary. I have been an Oura user since the early days. This dispute is interesting yet fails to address the fundamental issue that zero wearables are accurate for HRV and sleep stages.

The medical community with their hundreds of thousand of dollars of testing equipment is at odds with wearable sleep stages? So when you connect sensors all over my body including my head to measure brain waves and then put me in a unfamiliar, uncomfortable bed, in a labratory setting, and measure whatever fitful sleep I get for one night, THAT is the standard?

Measuring sleep stages/phases is messy at best. In an absolute best-case study-like scenario, you’re looking at accuracy in the mid-80% range. Part of the challenge is that the actual assignment of sleep phases/stages is done by a human, and how different humans make these assignments varies quite a bit, and vary in accuracy. There’s some interesting studies that actually look at the accuracy of this grading.

That said, HRV is actually rather straight-forward (compared to sleep stages). You’ve basically got two camps of HRV tracking:

A) The do it all night long camp (how almost all wearables do it)

B) The do it manually in the morning camp (how some people do it)

There’s pros and cons to both methods, which is best reserved for a different post/comment. But either way, I don’t actually see much disagreement with method A above between wearables.

Hey Ray,

just a little side note to the HRV discussion above: there are actually some substantial differences in HRV tracking, the biggest one being that Apple uses SDNN whereas everybody else (as far as I know) uses RMSSD to calculate the mean of inter beat intervals.

The practical difference is that HRV as calculated by Apple is usable mostly as a health/longetivy metric (it is basically the gold standard in clinical studies) whereas others HRV is more useful as an acute recovery/stress metric (where the data is honestly less clear as there is obviously way more grant money in predicting heart attacks as opposed to predicting 5k race time).

The next time you find yourself on an 15-hour flight, this is a nice overview link to ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

True, I didn’t want to dive into the differences in how Apple does it in this case of SDNN vs RMSSD. That said, we’ve seen plenty of apps leverage SDNN on the Apple Watch to use that data in the same way as everyone else using RMSSD.

Yeah, I wonder how accurate it can be as the data base simply doesn’t lend itself to short term predictions. That being said, I wouldn’t put it past Apple to come up with some useful model leveraging all the other sensors (temperature and sleeping HR seem like prime candidates) as well to actually come up with a recovery number much more accurate than what HRV provides.

Wouldn’t want to be a Morpheus shareholder in that case :-)

When I read this post I think “What the f*ck are these guys at the patent office do?”

Take no offence, patent office employees, I am no expert in this field so you might do you job very well.

I do understand from this and other articles that it is ultimately a judge who determines if a patent is valid. I then assume that the patent office was installed to do the checks the judge would do already when the patent is requested. And if the patent office then does its job well, the judges would follow the patent office almost always.

But in my view, reinforced by this post, that is not true. The arguments of the patent office are sometimes (too often?) too flaw to give a patent, since judges wipe them from the table easily. As dcrainmaker texts are already used in legal contexts as I just read, let me also do that and quote above post: “…when patents are being issued that really shouldn’t. In that case, the judge questioned many times the validity of some components of the patents, …”.

Who can give more info on the effectiviness of the work of the patent office?

I’m interested. Like I said I am not an expert. But it does look weird to me.

That’s not quite how it works – the patent office reviews and issues the patent – a judge will only look at it if it is challenged.

The issue is that patent offices deal with 100,000s of applications and don’t have the capacity to do their own prior art searches etc. and so are taking the patent applicants submissions in good faith – issues will only come to their attention if someone objects at the point of grant – which you might not in 2016 when you have no plans to make a smart ring in 2024.

Yes, a lot of patents are a bit junky, but its difficult to get round that without massively up-resourcing patent offices the world ove!

But that is how it works, and that is what you write: “… the patent office reviews and issues the patent – a judge will only look at it if it is challenged.”. I have the idea that judges too often say that patents are given on false grounds – and this post reinforces my idea here. But I am not an expert like I said.

Or stated as a question: how would you measure the effectiveness of the patent office?

I think how judges approve or disapproves them are a good KPI.

About your remark: “The issue is that patent offices deal with 100,000s of applications and don’t have the capacity to do their own prior art searches etc. and so are taking the patent applicants submissions in good faith”

That sounds scary to me. Companies pay lots of money to the patent office for intellectual property. Are you now saying that that is not worth much, because the office has too much work?

You misunderstand the main function of the patent office: It functions primarily as a registry to record patent filings (and assessing that they follow proper form, process, etc.), NOT to evaluate the merits of the application/substance of the patent or whether it is valid (is it original or does prior art exist, etc.).

That way, IF there is a dispute at some point over IP rights, it is very clear when somebody filed for patent protection and exactly for what.

So the affirmation/revocation rate by the courts is not a good KPI at all for the performance of the patent office.

That’s not true at all – the vast majority of patnet offices do their own searches. The ones which do not are in smaller markets (South Africa, Belgium, etc). The USPTO absolutely does do a search on every single patent application which is submitted for examination. Same for Europe, China, Korea, Japan, etc etc.

“yield its massive army of lawyers” maybe “wield its massive army of lawyers,”? Good read

Thanks!

I’ve highly appreciated the scientic and analytical depth of your reviews over the years but this time I was pretty disappointed to see that for some reason you did not want to dig deeper to really understand the facts before giving your analysis and claiming something on pretty soft basis:

“…said recovery-type algorithms have been around long-before the smart ring concept. We’ve seen those from numerous players over the years including Garmin, Firstbeat, Polar, Suunto, and others of the pre-2016 era. None of that is new, but adding data coming “from a smart ring is”, supposedly, “new” enough to have been granted a patent for “readiness score”.”

None of these companies’ “recovery-type algorithms” are even close to Oura’s readiness score in practice. It is a very false statement to say that the only new thing is “adding data coming “from a smart ring”. I thought you could do more thorough work in this or at least would try since you have all the capabilities to do so.

This comments really misses the mark:

1. The discussion is about the scope of the patent, not what the different algorithms actually do in in practice. The language in th patent does not describe anything that these competing offerings have not been doing for years already.

2. Even if we shift the topic of disucssion to what the products actually do, your post provides zero specific arguments on why and in which way the Oura algorithm supposedly is different (and presumbaly superior). It is just a sweeping statement without any detail – let alone evidence to back it up.

Indeed, this is about the patent, and the patent actually doesn’t go beyond what competitors offered. You asked for details, and I literally highlighted the exact line from the patent application on what’s included. The only thing that made their patent unique was saying ‘the data came from a smart ring’, everything else was run of the mill at that point, in terms of, again, what’s actually in their patent application.

While Oura has more in its score today than the patent application, that doesn’t make what they have today meaningful from a patent standpoint.

That said, if you want to get into the actual current-state tech, no, Oura isn’t close to what Garmin has these days from a “Readiness” standpoint (specifically, the number of factors Garmin includes, primarily around workout data), nor what even Fitbit or Whoop does for that matter. This is because both Fitbit and Whoop are looking at the workout side more heavily. While Oura says they include “Activity” details based on intensity, my testing over the last few years, shows it’s much more heavily skewed towards calories than intensity.

Oura is good at sleep tracking, and has been. But frankly, so are most other players these days. Everyone likes to say Oura is “good at sleep tracking”, and that’s fine, but that ignores the point that they’re iffy at workout tracking (works for some people, doesn’t work for others). And you can’t have one without the other, if you’re looking at readiness tracking.

Look, Oura does cool stuff (especially fertility and period prediction), but the rest of the industry has been slowly passing them by in most other areas. Oura has taken the approach of using lawsuits, rather than focusing on tech.

Also, since I just Google’d your name, Petteri Lahtela, I noticed you’re one of the co-founders of Oura.

Assuming that’s you, since you posted from Finland with a seemingly real-looking e-mail address…wow….I have so many questions on this comment. But more importantly, as I said above, you really need to understand and use your competitors better. Because frankly, it appears you’ve got no idea what you’re competitors are doing in this space.

Your comment (assuming it’s you), sounds just like Garmin did versus Wahoo years ago on new bike computers, or inversely, just like Wahoo did against Garmin as Wahoo started to slide behind again. One can easily look up how that ended.