Heads up – Massive Sports Tech Holiday Deals List is Live!!! The Garmin Fenix 8 is $250 off (even the Fenix 8 Pro is $100 off!), the Apple Watch Ultra 3 is on sale, the Garmin inReach Mini 2 is $249, the GoPro Hero 13 Black, DJI NEO, and a ton of other brands/deals, including Wahoo, Oura, Whoop, Polar, Samsung, Google, and more than 100 sports tech deals here!

I’m DC RAINMAKER…

I swim, bike and run. Then, I come here and write about my adventures. It’s as simple as that. Most of the time. If you’re new around these parts, here’s the long version of my story.

You'll support the site, and get ad-free DCR! Plus, you'll be more awesome. Click above for all the details. Oh, and you can sign-up for the newsletter here!

Here’s how to save!

Wanna save some cash and support the site? These companies help support the site! With Backcountry.com or Competitive Cyclist with either the coupon code DCRAINMAKER for first time users saving 15% on applicable products.

You can also pick-up tons of gear at REI via these links, which is a long-time supporter as well:Alternatively, for everything else on the planet, simply buy your goods from Amazon via the link below and I get a tiny bit back as an Amazon Associate. No cost to you, easy as pie!

You can use the above link for any Amazon country and it (should) automatically redirect to your local Amazon site.

While I don't partner with many companies, there's a few that I love, and support the site. Full details!

Want to compare the features of each product, down to the nitty-gritty? No problem, the product comparison data is constantly updated with new products and new features added to old products!

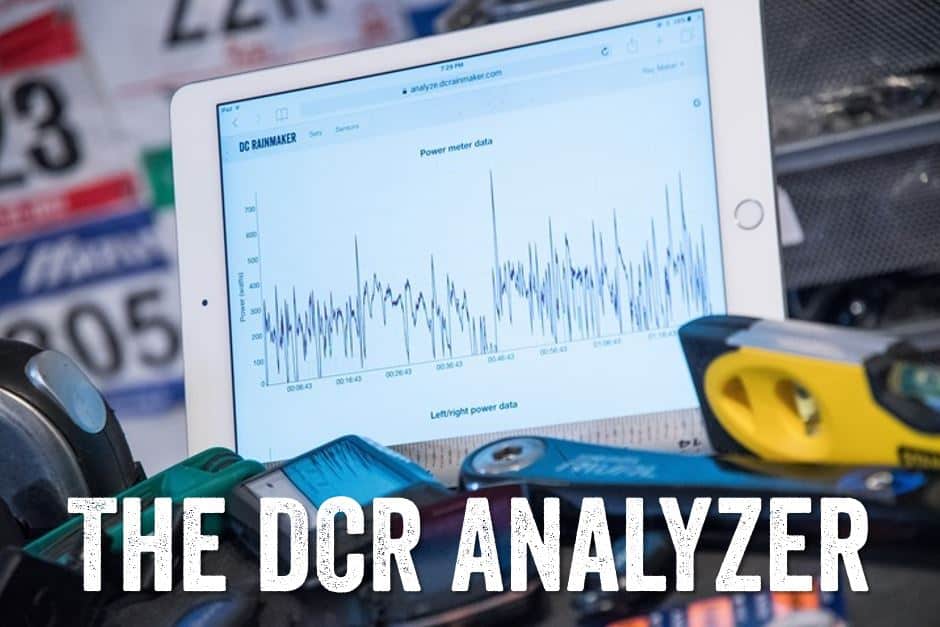

Wanna create comparison chart graphs just like I do for GPS, heart rate, power meters and more? No problem, here's the platform I use - you can too!

Think my written reviews are deep? You should check out my videos. I take things to a whole new level of interactive depth!

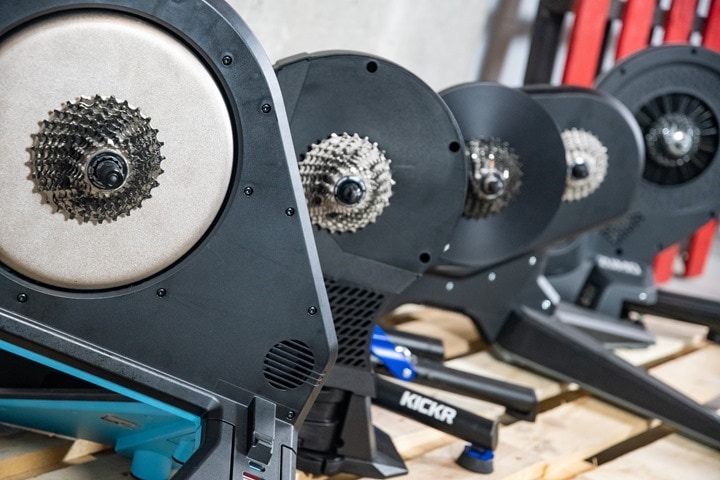

Smart Trainers Buyers Guide: Looking at a smart trainer this winter? I cover all the units to buy (and avoid) for indoor training. The good, the bad, and the ugly.

-

Check out my weekly podcast - with DesFit, which is packed with both gadget and non-gadget goodness!

Get all your awesome DC Rainmaker gear here!

FAQ’s

I have built an extensive list of my most frequently asked questions. Below are the most popular.

- Do you have a privacy policy posted?

- Why haven’t you yet released a review for XYZ product you mentioned months ago?

- Will you test our product before release?

- Are you willing to review or test beta products?

- Which trainer should I buy?

- Which GPS watch should I buy?

- I’m headed to Paris – what do you recommend for training or sightseeing?

- I’m headed to Washington DC – what do you recommend for training?

- I’m from out of the country and will be visiting the US, what’s the best triathlon shop in city XYZ?

- What kind of camera do you use?

-

5 Easy Steps To The Site

In Depth Product Reviews

You probably stumbled upon here looking for a review of a sports gadget. If you’re trying to decide which unit to buy – check out my in-depth reviews section. Some reviews are over 60 pages long when printed out, with hundreds of photos! I aim to leave no stone unturned.

Read My Sports Gadget Recommendations.

Here’s my most recent GPS watch guide here, and cycling GPS computers here. Plus there are smart trainers here, all in these guides cover almost every category of sports gadgets out there. Looking for the equipment I use day-to-day? I also just put together my complete ‘Gear I Use’ equipment list, from swim to bike to run and everything in between (plus a few extra things). And to compliment that, here’s The Girl’s (my wife’s) list. Enjoy, and thanks for stopping by!

Have some fun in the travel section.

I travel a fair bit, both for work and for fun. Here’s a bunch of random trip reports and daily trip-logs that I’ve put together and posted. I’ve sorted it all by world geography, in an attempt to make it easy to figure out where I’ve been.

My Photography Gear: The Cameras/Drones/Action Cams I Use Daily

The most common question I receive outside of the “what’s the best GPS watch for me” variant, are photography-esq based. So in efforts to combat the amount of emails I need to sort through on a daily basis, I’ve complied this “My Photography Gear” post for your curious minds (including drones & action cams!)! It’s a nice break from the day-to-day sports-tech talk, and I hope you get something out of it!

The Swim/Bike/Run Gear I Use List

Many readers stumble into my website in search of information on the latest and greatest sports tech products. But at the end of the day, you might just be wondering “What does Ray use when not testing new products?”. So here is the most up to date list of products I like and fit the bill for me and my training needs best! DC Rainmaker 2024 swim, bike, run, and general gear list. But wait, are you a female and feel like these things might not apply to you? If that’s the case (but certainly not saying my choices aren’t good for women), and you just want to see a different gear junkies “picks”, check out The Girl’s Gear Guide too.

Great post Ray! I have a 500-700 foot climb home (depending on the route I take) after work every day so climbing technique is always on my mind. I think I’m probably similar to you too in that I’d do better on a hilly course than a flat one. Lately I’ve been powering up the climb home with slow cadence and a lot of standing, this post was a good reminder that I need to mix things up and work on higher cadence again to maximize my efficiency.

Ray, thanks for another great post. Climbing technique is one of my favorite topics. It is nice to see that your conclusions fit in with my unscientific/empirically determined methods, i.e., what “feels” right. I have a similar situation, I am weaker on the flats but climb pretty well(at least I think so)compared to others in our riding group. I have always believed that you should use the descents to recover rather than push even harder. On a different topic, I would be interested to hear about any stretching routine that you use post race. Again, thanks for maintaining such a great blog!

I always spin fast going up a hill, then kick it on the downhill. Which is why, I believe, I am always getting passed going up a hill :-) of course, having a lighter bike with better components might help…

This is an amazing post. The entire time I read it, I was thinking about Joe Friel’s blog on this topic. Then you mentioned him.

Thanks for spelling this out so clearly. Too bad IMAZ doesn’t have any hills.

Good points all around. As a fellow climber, I’ll chime in.

* You state that HR goes up with lower cadence, but I’m not entirely sure this is correct. In general a fast spin (85-105 rpm) will tax the cardiovascular system and increase breathing while giving relief to the major muscles. In contrast, a slower spin (55-75) will work the muscles harder and the primary risk is fatigue and lactic acid build up.

* HR definitely goes up if you stand, so do it wisely.

* Excellent point about managing time/effort on the summit. I was always taught to ride through the crest, not toward it.

* On a related note, the begin of the descent is a useful place to punch the speed a little. If you had to choose to put effort into the descent on one third of the downhill section, the upper most section will yield the biggest advantage. The reason is simple… you don’t have much wind resistance yet and the momentum created is helpful for more distance down the descent. So definitely rest up on the descent, but do so after cranking it up to speed near the top.

* A tip someone shared with me turned me from a hill survivor to a hill climber. Hold the top of the bars with your thumbs pointed inward toward the stem. Grip firmly and stabilize your upper body. When the going gets steep, imagine you are bending the bars backward with your grip. In doing this you will find that you recruit your mid-section muscles and it is a little easier to get the peddles through the 12 o’clock position with force.

Great article again.

Physics says air drag goes up with the square of speed. So to double your speed you need to use twice the energy. Obviously there are many other factors and air drag also depends on your body position, but as a sweeping statement in terms of drag you are always best to keep to the same speed, rather than going faster or slower.

Ps I know this is simplication of the physics, but its pretty accurate honest!

Ray – Read your article before my Austin 70.3 and applied the philosophy during my race. There aren’t too many hills on the course but I did manage to maintain a 21.63mph pace throughout the 56 miles with a .78 IF. Thanks for the good info.

Jim

Ray, Nice post. I am particularly interested in any additional advice you could give me on the RI 70.3. It will be my first 70.3 and is my “A” race for this season.

Thanks again.

Pity I didn’t see this article 5 years ago, but BIG thanks for the tips. As we don’t have any hills in The Netherlands I don’t have any experience with them. But a friend of mine cycles some hilly area in Limburg (the south) so I went along with her last summer.

It wasn’t a race, merely a friendly ride. And since all the girlfriends I was with never go faster than a paltry 17mph I thought it was fun, for me, to try and overcome the hills on 52/≈14. Most of the hills I did it like that, since they were all short and not really that steep. Of course, I had to stand up many times, and think this is where I got my calcaneal spur from. Never should have done those hills standing up. Walking hurts, running is out of the question.