Heads up – Massive Sports Tech Holiday Deals List is Live!!! The Garmin Fenix 8 is $250 off (even the Fenix 8 Pro is $100 off!), the Apple Watch Ultra 3 is on sale, the Garmin inReach Mini 2 is $249, the GoPro Hero 13 Black, DJI NEO, and a ton of other brands/deals, including Wahoo, Oura, Whoop, Polar, Samsung, Google, and more than 100 sports tech deals here!

I’m DC RAINMAKER…

I swim, bike and run. Then, I come here and write about my adventures. It’s as simple as that. Most of the time. If you’re new around these parts, here’s the long version of my story.

You'll support the site, and get ad-free DCR! Plus, you'll be more awesome. Click above for all the details. Oh, and you can sign-up for the newsletter here!

Here’s how to save!

Wanna save some cash and support the site? These companies help support the site! With Backcountry.com or Competitive Cyclist with either the coupon code DCRAINMAKER for first time users saving 15% on applicable products.

You can also pick-up tons of gear at REI via these links, which is a long-time supporter as well:Alternatively, for everything else on the planet, simply buy your goods from Amazon via the link below and I get a tiny bit back as an Amazon Associate. No cost to you, easy as pie!

You can use the above link for any Amazon country and it (should) automatically redirect to your local Amazon site.

While I don't partner with many companies, there's a few that I love, and support the site. Full details!

Want to compare the features of each product, down to the nitty-gritty? No problem, the product comparison data is constantly updated with new products and new features added to old products!

Wanna create comparison chart graphs just like I do for GPS, heart rate, power meters and more? No problem, here's the platform I use - you can too!

Think my written reviews are deep? You should check out my videos. I take things to a whole new level of interactive depth!

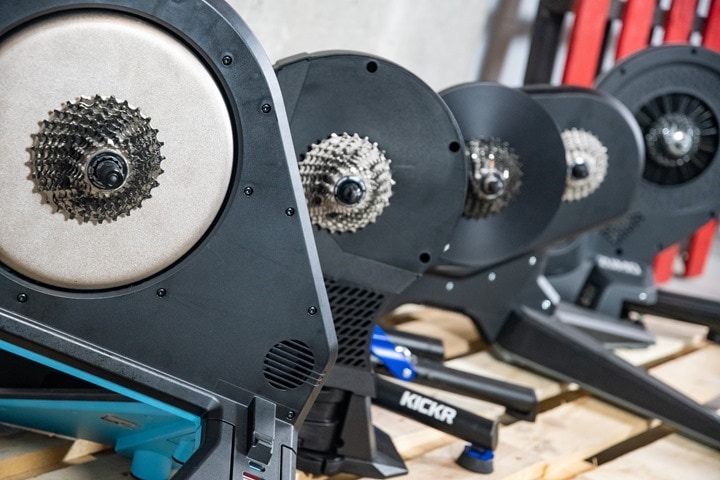

Smart Trainers Buyers Guide: Looking at a smart trainer this winter? I cover all the units to buy (and avoid) for indoor training. The good, the bad, and the ugly.

-

Check out my weekly podcast - with DesFit, which is packed with both gadget and non-gadget goodness!

Get all your awesome DC Rainmaker gear here!

FAQ’s

I have built an extensive list of my most frequently asked questions. Below are the most popular.

- Do you have a privacy policy posted?

- Why haven’t you yet released a review for XYZ product you mentioned months ago?

- Will you test our product before release?

- Are you willing to review or test beta products?

- Which trainer should I buy?

- Which GPS watch should I buy?

- I’m headed to Paris – what do you recommend for training or sightseeing?

- I’m headed to Washington DC – what do you recommend for training?

- I’m from out of the country and will be visiting the US, what’s the best triathlon shop in city XYZ?

- What kind of camera do you use?

-

5 Easy Steps To The Site

In Depth Product Reviews

You probably stumbled upon here looking for a review of a sports gadget. If you’re trying to decide which unit to buy – check out my in-depth reviews section. Some reviews are over 60 pages long when printed out, with hundreds of photos! I aim to leave no stone unturned.

Read My Sports Gadget Recommendations.

Here’s my most recent GPS watch guide here, and cycling GPS computers here. Plus there are smart trainers here, all in these guides cover almost every category of sports gadgets out there. Looking for the equipment I use day-to-day? I also just put together my complete ‘Gear I Use’ equipment list, from swim to bike to run and everything in between (plus a few extra things). And to compliment that, here’s The Girl’s (my wife’s) list. Enjoy, and thanks for stopping by!

Have some fun in the travel section.

I travel a fair bit, both for work and for fun. Here’s a bunch of random trip reports and daily trip-logs that I’ve put together and posted. I’ve sorted it all by world geography, in an attempt to make it easy to figure out where I’ve been.

My Photography Gear: The Cameras/Drones/Action Cams I Use Daily

The most common question I receive outside of the “what’s the best GPS watch for me” variant, are photography-esq based. So in efforts to combat the amount of emails I need to sort through on a daily basis, I’ve complied this “My Photography Gear” post for your curious minds (including drones & action cams!)! It’s a nice break from the day-to-day sports-tech talk, and I hope you get something out of it!

The Swim/Bike/Run Gear I Use List

Many readers stumble into my website in search of information on the latest and greatest sports tech products. But at the end of the day, you might just be wondering “What does Ray use when not testing new products?”. So here is the most up to date list of products I like and fit the bill for me and my training needs best! DC Rainmaker 2024 swim, bike, run, and general gear list. But wait, are you a female and feel like these things might not apply to you? If that’s the case (but certainly not saying my choices aren’t good for women), and you just want to see a different gear junkies “picks”, check out The Girl’s Gear Guide too.

Do you know if the changes in cadence affected their bike finishing time? I mean, it seems like saving a couple of minutes on the run is worthless if your bike time is slower…

It seems that if we find one study, we just need to wait a bit and another study will provide us with the opposite conclusion.

I’m a 92 cadence guy, my legs are just too big to do the whole over 100 thing.

I found that if I eliminate the cycling portion of the race, my run splits are much faster.

Squirrels suck, kill all the little Mother Fu@$ers :)

Nice new ride, don’t be “ghetto” like me and race with training wheels on a beautiful Aero machine.

Love the Zipps!!!!!!!!

Interesting stuff, inconclusivly my natural bike cadence is 80-85 and my run one is the same…kinda spooky, was I a bike in a former life?

How does a researcher control for all the variables in a study like that? It seems to me the reason the results are divergent is because controlling for everything in a race situation is too difficult. How would you even set up that experiment?

I’m with danielle on this one..

good point…

well, thanks for sharing!

:)

Interesting notion, how to fit the bike/run efforts together so you maximize both. And the answer is…?

There’s a lot we still don’t know about the world around us, and that includes our own bodies. But that doesn’t mean we can stop learning – in fact, it only means we need to be even more diligent in our research. As scientists uncover new facts about how the body works, they are able to develop better treatments for various health conditions. And as these treatments become available to more people, their quality of life will improve significantly.