Over the years I’ve often dug into the behind the scenes technical aspects of the biggest cyclist races in the world. From rider live tracking to the facilities that TV broadcasters use to get that race coverage to you. And today, I’m going to do the exact same thing for the Virtual Tour de France, which wraps up this weekend with two final stages – one up Mont Ventoux and then the finale in Paris.

And whether or not you find watching virtual cycling entertaining, I suspect you’ll still find this technology aspect interesting. What started off as a quick piece on Zwift’s new RaceView quickly unraveled into a deep dive into the technology they use to work with real TV broadcasters to send out to millions of TV’s around the world.

As you’ll quickly find out, this isn’t your grandfather’s Zwift app. The tools the company has developed over the last year or so to support broadcasting of races beamed to millions of TV’s make it massively different than their first TV broadcast in January 2019. And even substantially different than live races of just a few months ago. Within this I’ll dive into the special version of Zwift that they use to set upwards of 140 cameras upon a race route, plus the hardware that it all runs on. Plus, I look behind the scenes at the three-country real-time broadcast tango that occurs on race day to consolidate that feed to more than 130 countries around the world.

And the last half of the post I dig into the new RaceView site, where you can watch/track the riders in real-time (even faster than the live streams in fact). So, let’s get rolling.

The Virtual TdF Broadcast:

The quantity of video streams that feed into the recent virtual TdF stages is mind-boggling. There’s upwards of 90 webcam feeds coming in from riders, some 140 virtual cameras placed within Zwift, and 8 concurrent camera angles rendering at any one time. Oh, and that’s before we even account for three different broadcast teams working across three countries concurrently for any given live broadcast. And that also ignores the teams of people that help riders prepare their setups and validate connections.

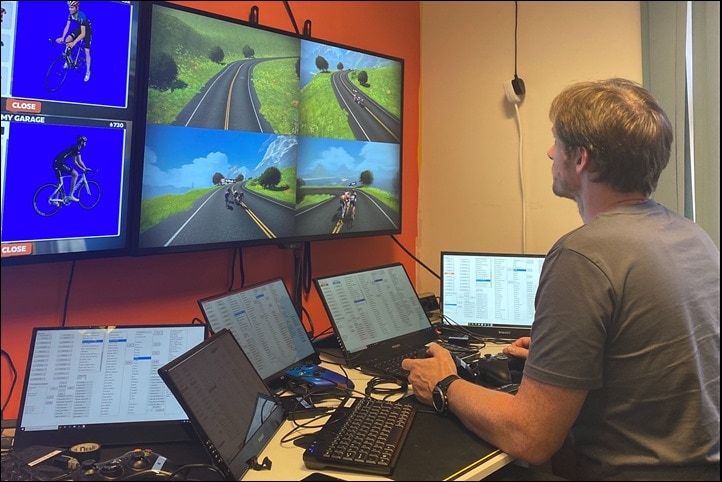

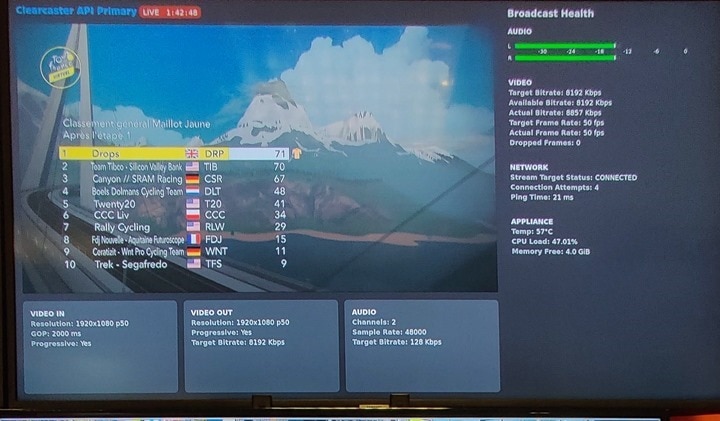

To begin, everything first starts from Zwift’s main broadcast facility in Edinburgh (UK). It’s here that Zwift is running 8 concurrent Intel Hades Canyon NUC’s with Radeon RX Vega M GPU’s, each running a special version of Zwift configured in Ultra mode with their frame rates locked at 50 frames per second.

At this point, some of you are like…but why NUC’s? Well – the answer to that is more practical in nature. In a pre-COVID era, they’d actually pack up the entire broadcast kit and go to events physically. So in that case having the smaller NUC form factor made much more sense.

In any event, each of these 8 machines are what Zwift refers to as the ‘Gameplay’ side. Meaning, they’re rendering in real-time the game of Zwift, mostly just like your Zwift at home. Whereas aspects like video from riders or commentators comes in later. These 8 machines are split up into four for the women’s race, and four for the men’s race. Keep in mind that while these races happen back to back for us viewers, for Zwift, they’re basically concurrent from a prep standpoint. Meaning, they’ll have the women racing while the men are getting into the game and getting set in the corral. As such, they’re treated as separate entities.

Each of these Intel NUC machines is then connected via HDMI which is in turn converted to SDI, and then into a Blackmagic ATEM 4 Broadcast Studio 4K switcher. Later, they’ll use a Blackmagic ATEM Television Studio Pro 4K Live Production Mixer to control the inputs, which is where they determine the semi-final Gameplay output feed. But that’s putting the cart way in front of the horse. See, while I just showed you where the cable ran, that skips the best part: The special sauce software.

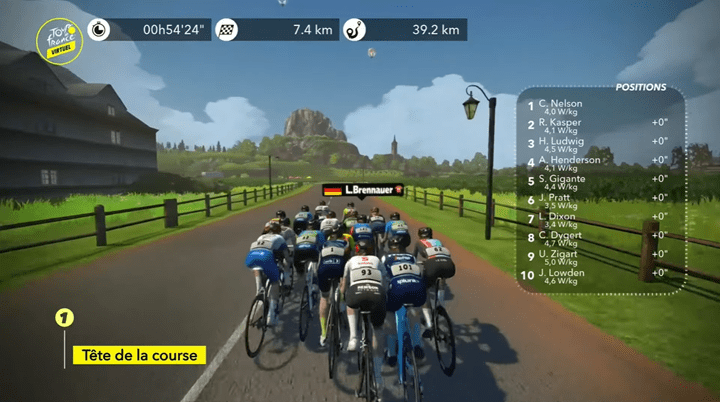

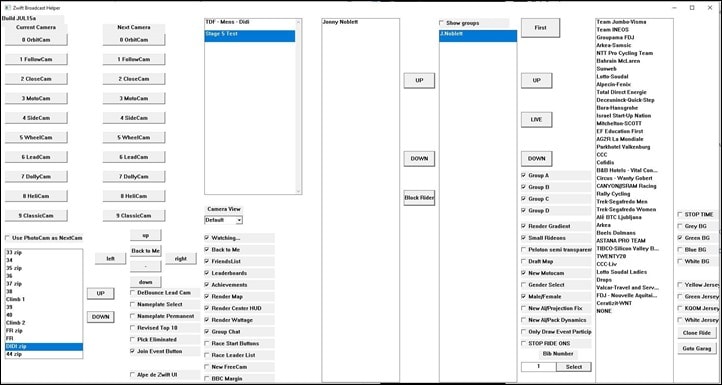

See, Zwift has a special Zwift Broadcast version of the game that includes the normal main Zwift window, but then has a secondary helper window that controls the camera angles. For example, on your home version of Zwift you can press the 1 through 9 (plus 0) number keys to change views. But in this version they’ve got the ability to trigger predefined camera paths, predefined camera shots, and variable camera shots. And again, all this is running eight times, once on each Intel NUC.

Within the Zwift Broadcast Helper window, there are basically four core shot types that Zwift has:

A) Static Shots: These are just like in a real cycling race where a camera is mounted to a specific place and the riders ride past it

B) Follow Shots: These shots follow not just a given rider, but also can be called for a given variable place (like yellow jersey, polka dot, leader, etc…)

C) Zipline Shots: These are when the camera is on a zipline between two points, and follows the action in front of it (typically tied to a given rider/placement)

D) Spline Shots: These are the most complicated shots, and are basically Zipline shots with multiple camera moves inside them. Basically, swanky drone shots.

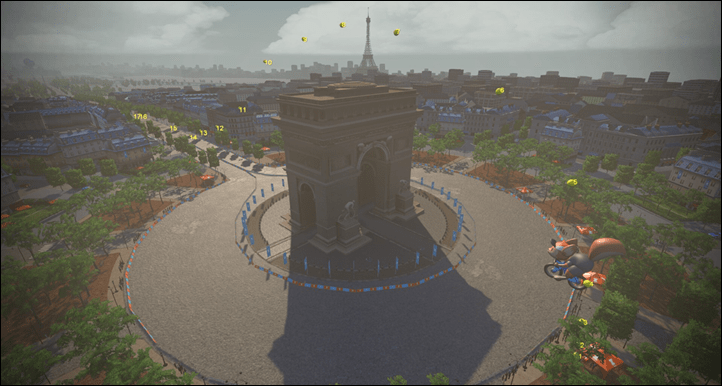

Here, the below is an example of a special spline shot that you’ll see below in this weekend’s finale in Paris. What you want to take note of specifically is the yellow numbers points. That’s showing the exact spots the camera will pass through. This is where Zwift can pre-program the camera for when the riders come through.

And here’s an early render of what that shots will look like on Sunday:

On any given route in the Tour de France, Zwift is programming upwards of 140 camera positions in ahead of time These are ordered just like the actual race route itself, so they iterate through them as they go through the route. In the below screenshot you can see in the lower left the numbering next to each camera. You’ll also see numerous options for whether to overlay certain status. Also, normally the list of riders is shown in the middle columns, though isn’t on this specific screenshot.

Each of the four Intel NUC machines (one set for men’s and women’s) has a dedicated camera feed that it’s responsible for. This mirrors what you see in real-life, by the way. For Zwift, the four virtual cameras are roughly set up as:

NUC/Camera 1: Lead moto shot, typically looking back towards the peloton, but virtually tied to the current race leader

NUC/Camera 2: Sitting in peloton camera, and is typically virtually tied to a given race jersey wearer

NUC/Camera 3: Rider focused camera, such as during an interview, or discussing a given rider

NUC/Camera 4: Specialty camera, this is used for those zipline/spline/static special camera shots

So with those four feeds, Zwift has a small team that works together in the Edinburgh studio to prep and then change between the different angles. But each person has a specific role. First there’s a game-play operator. That person is controlling each of those NUC machines and setting up the shot that’s coming next. In other words, they’re a virtual cameraman. Oh, except controlling four concurrent cameras with more than 100 cameras to choose from.

But, that’s actually not the person who decides what you’ll see. Instead, there’s another person in that room, who is calling out which shots he needs next. Effectively a director, though in this production as you’ll see there’s also another director. But consider this the director of gameplay. That person then takes the shot, and changes to that shot with the ATEM switcher. You can see below in this photo Zwift sent over, the gameplay operator with the four camera angles, and four Zwift helper screens in front of them.

Oh – did I mention all of this is also recorded on a replay machine too? That takes all four of those feeds and records it for instant replay purposes.

Ok, so at this point we’ve finally got ourselves a final gameplay feed of Zwiftness, ready to go somewhere. But Zwift doesn’t actually broadcast it themselves for the Virtual Tour de France. Instead, they take that feed (which, is actually four feeds, including the replay feed) and transmits it to Paris, France.

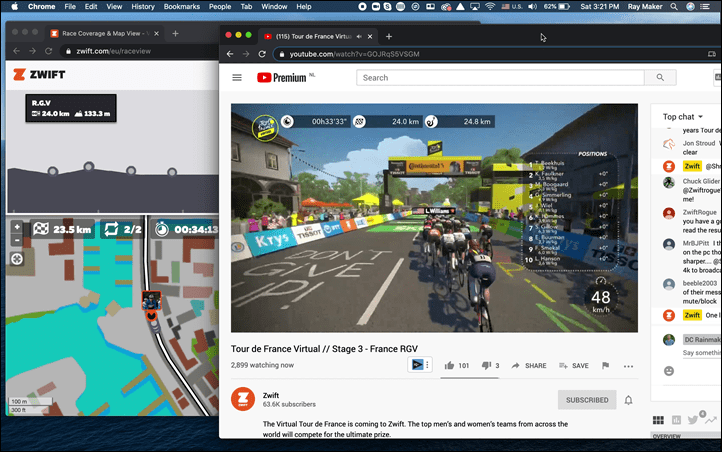

That’s where Euromedia takes control of the production that you ultimately see. See, at this point there are no titles (text) on the screen. It’s just underlying gameplay. Notice in the above video stream screenshots you don’t see any text. Instead, that all gets integrated in Paris.

It’s there that three different entities converge:

A) Zwift’s Gameplay feed of the action

B) All the 90 webcams from riders

C) All the titles/text overlays, from a Belgium company called Boost

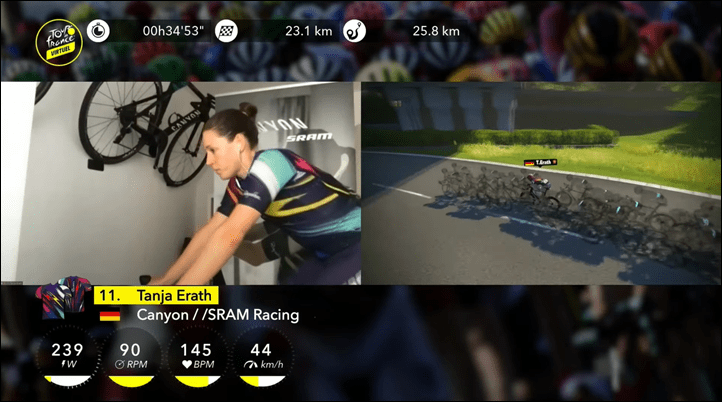

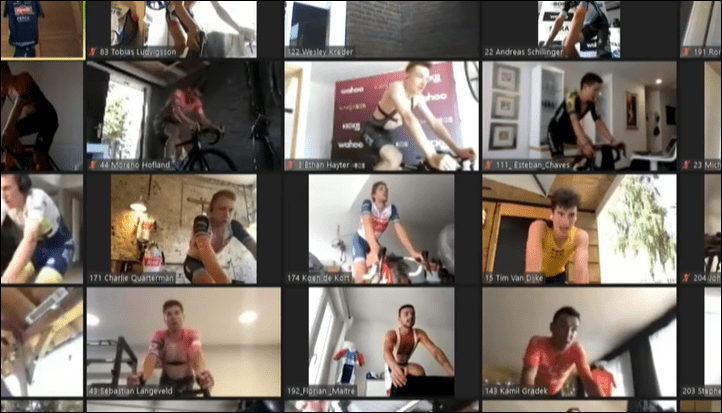

In Paris, another production team takes those three things and mixes them together. In fact, looking at the below shot pretty much shows this super well. The webcam from Tanja Erath is coming in via Zoom (more on that in a second), the Zwift screens are coming via the Gameplay feed from Zwift, and every bit of titles and text you see are coming from Boost in Belgium. All of it mixed in real-time in Paris at Euromedia.

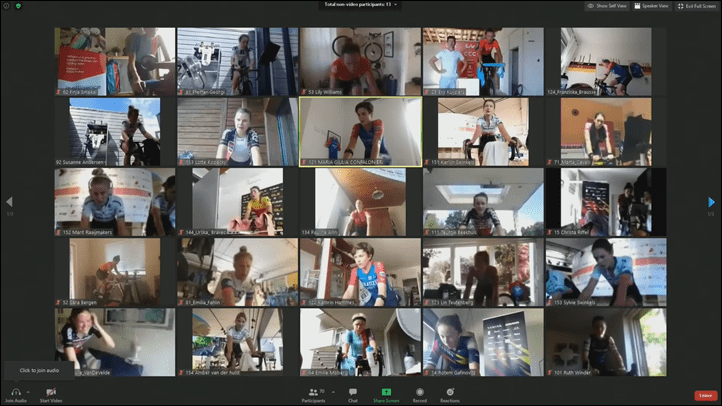

But wait a second, how do they get the rider video feeds? Well, turns out it’s one giant Zoom party. Seriously, it’s every rider (save the few who couldn’t figure out their webcams) Here’s a shot of one (of three) pages of the women’s race, note at the bottom the 70 riders as part of this Zoom call.

And here’s a shot of all three pages of the men:

This giant Zoom room of sweaty parties is how Euromedia cuts to each rider. As part of the conference they’ll specifically re-label each rider to be their rider number and then their name. Then, when a given rider is needed a person in Paris will select that rider and drag them to a separate screen which is pulled into the production just like any other video source.

Zwift says the vast majority of the riders have webcams, and for good reason: It’s good PR. We’ve seen everything from fairly basic rider camera setups, to fairly elaborate ones. Most take some stab at being on-point in terms of team/sponsor branding.

The Tour has some interviews already done ahead of time, so these will be woven into the story of the race – just like they do for real Tour de France races.

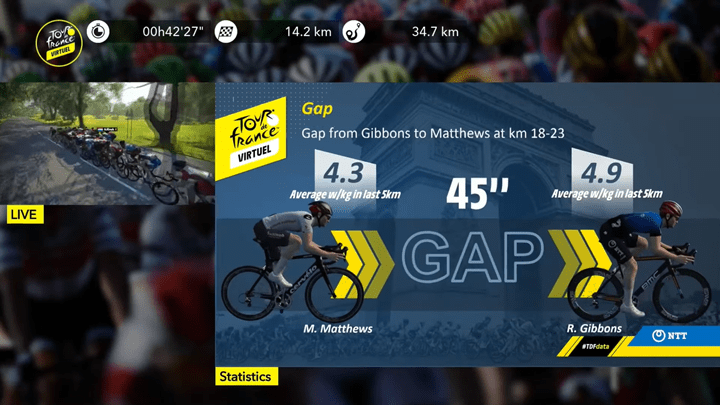

But wait, what about those titles? All that text stuff? Well, that comes from Boost, a Belgium company specializing in it. But there’s more than meets the eye there. See, on the below left image you’ve got race time, distance remaining, kilometers raced, plus some bits around the stage. But there’s also ones like below at right, showing wattage, cadence, heart rate, and speed. Plus the rider information.

See, all that is created using an internal Broadcaster API that Boost has access to. In fact, there are three core API’s that Zwift has:

A) Internal API: This has basically access to everything data-wise, but isn’t restricted because it’s fully internal to Zwift

B) Broadcaster API: This is what Boost and NTT use, and allows them access to details like rider power, cadence, heart rate, plus event metrics. In this case, riders that participate in the event have given consent for this information to be displayed via those agreements.

C) 3rd Party API: This is for ZwiftGPS, ZwiftPower, and a few others, where users have to opt-in to have their information shown.

It’s from this API that Boost gets all the information they need in real-time from the game, allowing it to match up with the near-real-time gameplay feed from the Zwift gameplay NUC’s. And, it’s this same API that NTT has access to, to generate data for the mid-race metrics, like below. These titles/graphics are still rendered by Boost, and then consolidated into data that Euromedia in Paris can leverage.

So, finally, the director in Paris takes all of this information in, and overlays the graphics for each shot (all in real-time), and then creates a final broadcast stream. At that point the stream is available to all of ASO’s broadcast partners for the event, since ASO runs the Tour de France. So for example Eurosport, or NBC, or whomever. They’ll add their own commentary in their own local languages. And in fact, the stream you might watch on YouTube on Zwift’s own channel is effectively just another broadcast partner.

Note that this is slightly different than a normal Tour de France wherein the larger broadcast entities (such as NBC or Eurosport) can also see all the live camera feeds and make their own production choices. And they also make their own title packages, etc… But for this year for Zwift and for this event, they’re handling it as a complete package.

And thus you see it a short bit later, in ideally decent quality. The quality is the one aspect that Zwift is still struggling with in some cases. It seems like what broadcast partners see is pretty sharp, however in some cases the stream quality we see on YouTube is much more muddled, as if the bitrate has been turned way down. So while the underlying quality of the render is present on Zwift’s YouTube stream, the end-state artifacting needs some work. After all, if GPLAMA can broadcast a crispy HD stream live on a single PC of the same game, then certainly Zwift can achieve that with much more gear and broadcast facilities.

And Zwift says they’re working on it, and specifically trying to see if it’s the additional hops taken after leaving the Paris production facility back to Zwift’s own facilities that are causing it.

Still – that’s a relatively minor thing to sort out in the grand scheme of things. What’s more notable I think today is just how far Zwift has come since that first TV broadcast last year. Sure, it’s still the same Zwift – but the broadcast work around it makes the act of watching virtual cycling so much more viable than it used to be. And if we look ahead to Zwift’s oft-stated goal of having Zwift in the Olympics in 2028, then that’s another 8 years of potential improvements to not just the broadcast, but also the way events are raced.

RaceView Live Tracker:

If you’ve ever watched the real Tour de France (because, of course you have), you’ve probably seen stats and live tracking of the riders. Ironically, that in and of itself has a long and storied history of technological prowess depending on who was in charge at the UCI at the time. But we’ll set that aside for the moment and focus just on the Zwift variant.

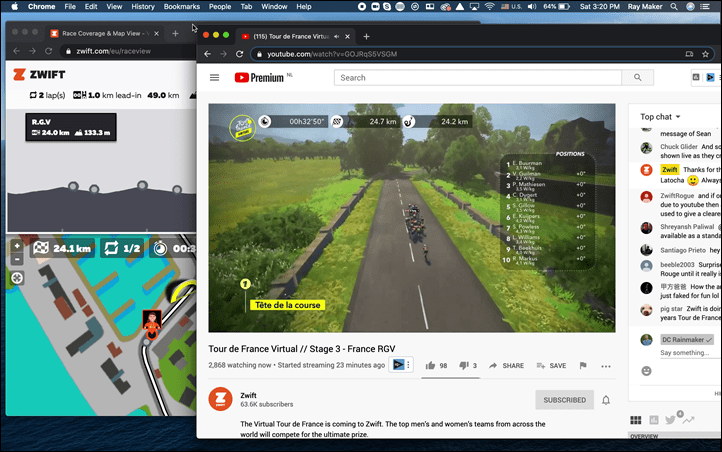

Two weeks ago, Zwift quietly released a new publicly accessible race tracking site called RaceView, which allows you to see the exact positions of riders in Zwift, all without ever logging into Zwift (or even watching the broadcast). I had first noticed the site in a tweet from Hannah Walker, and then a few days later saw a quick overview from Zwift Insider.

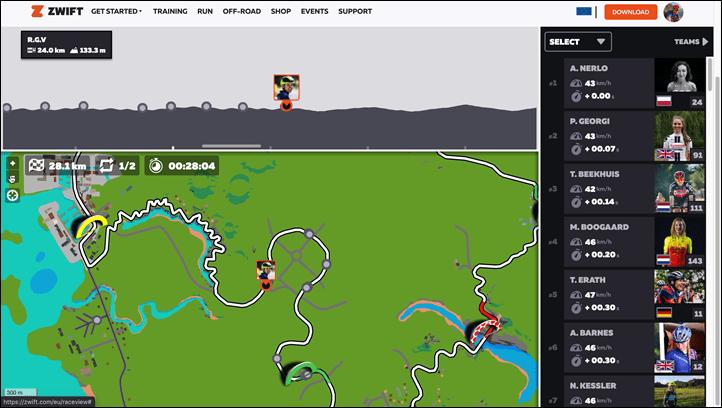

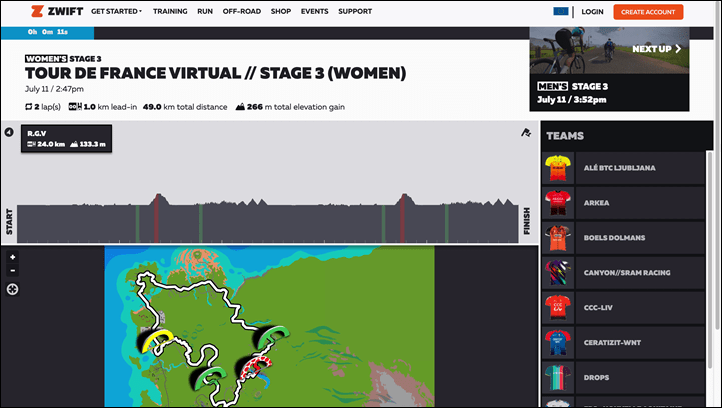

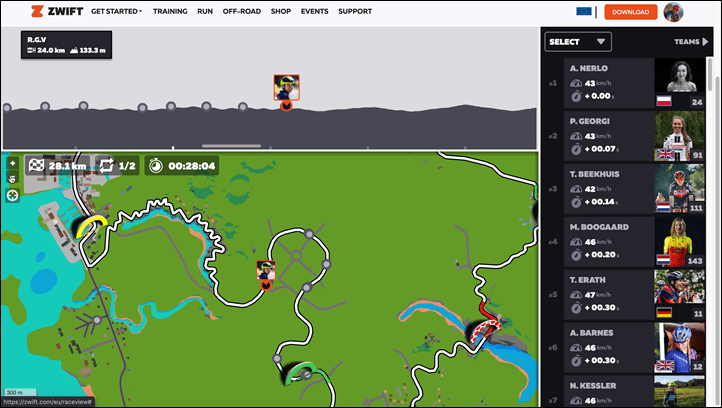

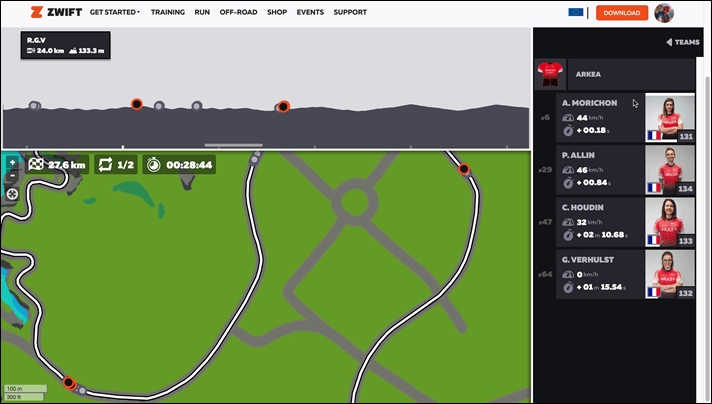

But as always, I was looking for more details – so I hit up Zwift and got a bit of insight on the motivation behind it, the target audience, and where they saw it going. However, if you haven’t seen it – then simply bookmark Zwift.com/Raceview ahead of this weekend’s Virtual Tour de France actual. It’ll be live for both the pro men’s and women’s races. Once loaded up, this is what you’ll see:

Along the top is the current stage information, including laps, portions of course details (such as lead-in information), as well as total distance and elevation gain. Next, you’ll see a course elevation profile, and below that a map of the Zwift world with the route. There’s also sprint/KOM/finish markers. And finally, along the right side you’ll see the team or riders listed, depending on the exact view you’re in and when you join in. Before the start of the race you’ll see the teams, but after the race begins you’ll see individual riders and their current race position:

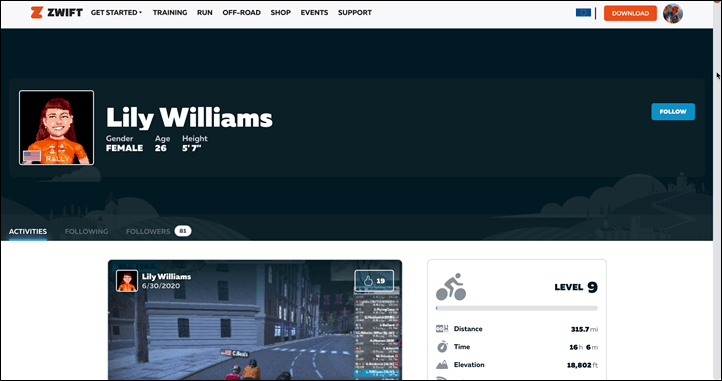

If you click on a given rider on the right, it’ll zoom in to their position on the map. Each dot on the map represents a given rider, though at present you can’t just click on a dot to see who has fallen off the back. Zwift says that’s something that’ll probably come.

When you click on a rider, it’ll show their Zwift profile – and you can see some of the same general information you might see in the Zwift Companion App, including their Zwift level and recent activities.

Back on the dashboard when you toggle into team mode you can see all members of the team racing, and their dots turn orange on the map. You’ll also see their speed and placement:

There’s also a drop-down that lists all riders alphabetically too, in case you’re trying to find a specific rider and can’t remember their team-name.

So – who was this designed for? Well, surprisingly not the commentators, as I presumed it was. Instead, it was actually designed for fans – or basically, you and I. The idea being you could have a tab/device opened while watching the race, to try and keep track of where people are. And in theory, that kinda works:

It’s viable for seeing the general gist of things, or if someone has fallen way off the back. But it’s also hard to match up with the race. Due to the latency of watching the stream, what you see in RaceView is actually quite a bit ahead of the stream. You can see that below, where RaceView shows this group already in town, while online via YouTube they’re off in flower fields somewhere.

If you look at the race times, you’ll see there’s a gap of nearly 80 seconds, which…is crazy!

Zwift says this is something they’re looking into the best way to address this. It’s also notable for commentating folks, where I originally saw the platform being used.

The biggest gaps I saw though were lack of other metrics. For example, in the livestream we’ll see power, heart rate, and cadence. But none of those are shown in RaceView today. Zwift says they’re considering adding those, plus metrics like current grade of a given rider.

After all, those metrics could be just as valuable to a given team’s director as the riders. To be able to see that a given rider is suffering up an 8% grade section as the reason they’re going slower is helpful, especially at a simple dashboard glance.

At present, the RaceView site is really only being used for major headliner events, and hasn’t been used for any other events in between the Virtual Tour de France pro events. Though, it might not always be that way. Zwift says they’re working to finalize some other improvements and features in RaceView before they figure out to what extent it could be scaled up and used in other events.

Still, even in its infancy, it’s a handy little site if you’re trying to follow the action.

With that – thanks for reading, and hope you enjoyed geeking out a bit on all the technical details behind everything. Have a good weekend ahead, and the last two sets of races start at roughly 3PM Central European Time (9AM US Eastern Time) on both Saturday and Sunday.

FOUND THIS POST USEFUL? SUPPORT THE SITE!

Hopefully, you found this post useful. The website is really a labor of love, so please consider becoming a DC RAINMAKER Supporter. This gets you an ad-free experience, and access to our (mostly) bi-monthly behind-the-scenes video series of “Shed Talkin’”.

Support DCRainMaker - Shop on Amazon

Otherwise, perhaps consider using the below link if shopping on Amazon. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. It doesn’t cost you anything extra, but your purchases help support this website a lot. It could simply be buying toilet paper, or this pizza oven we use and love.

They just need Nathan Guerra.

One of the issue of their camera viewpoints is that they are tied to specific riders, and lack position filtering. As the relative positions in the pack are not very stable – there’s stutter in there, as there is on rider bank angles – this makes the overhead or moto views stutter back and forth on the pack. Smooth it…

That, and the low visual quality of the overall virtual worlds. They have obviously spent a lot of efforts doing that Paris world, but you can see major accelerated construction work in the back as the viewpoint changes and the graphics engine struggles to fill the view. The compromises done to allow the game to run on a wide variety of platforms come to bite when using the same so-so engine to generate a broadcast.

Interesting, I felt like a number of the new zipline/preplanned camera angles in this past weekend somewhat removed that aspect, except in cases where they were targeting a specific rider.

I’ve been watching the Virtual TdF events (first time just watching a Zwift event) and it’s been … ok. Not the most exciting racing I’ve seen because most of the riders are eliminated early and there is really nothing to ride for for the riders that don’t make the front group. They might as well not be in the race and you never see them.

As was mentioned in the post, the video quality (that I’m seeing anyway) is far below what I see when I ride Zwift. The details are blurred and it’s often hard to see the rider’s names and numbers. It’s also not ideal that no one seems to know who won a sprint or finish until a replay is available (and sometimes even that doesn’t help too much).

While I like Zwift for indoor riding, if it was not for the fact that this is really the only bike racing going on right now, I don’t think I’d be tuning in.

Can’t help but think that the RaceView could be particularly useful for coaches and leaders of team/club/group rides. I imagine they’ve got a lot of load management to figure out before opening it up to heavier usage though.

Great read!

It’s hilarious how much effort Zwift is putting into broadcasting this race, with low-quality 2010-era visuals, which is something that nobody asked for, while doing next to nothing to improve the quality of the experience for their paying customers.

Yeah, it’ll be interesting to see where things go visual-wise. I think in some ways the TdF is really the first time I’ve started to think ‘Maybe it’s time for Zwift to seriously figure out where the next level of gameplay is’ from a visual standpoint.

On one hand they’ve gotta figure out how to balance the ability for anyone to run it on an iPad or whatever, but at the other end, people can throw serious GPU hardware at Zwift, and the experience doesn’t really change much. It doesn’t go from ‘Ok’ to ‘Holy mother of where’s my credit card!’. Instead, it kinda goes from ‘Ok’ to ‘Huh, I see an extra tree shadow’.

I also wonder how things like xCloud, Stadiia, and others play into that future. In my mind, I’d hope that Gen2 of Zwift is entirely built for the cloud and streaming. I just don’t see a scenario where 3-5 years out, that isn’t the norm. Just like people watch Netflix, YouTube, and everything else today fully online. After all, Zwift is a fully online experience.

Opnions about the graphics are clearly subjective, but I am completely satisfied with the graphics. I’d rather know that, thanks to the relative ease of rendering the graphics on modern hardware, an hour group ride is only going to consume 15-20% of my iPad’s battery, so it’s ok that I forgot to charge it last night. I’d far rather they invest programming effort to add new features, improve the interface, etc.

I think the simple, cartoonish graphics are rather charming.

and yet we are not able to ride another world without restarting the game… but i guess that’s not priority for a media and marketting focused company

Possibly the geekiest and one of the most interesting articles I have read on DCR. Great stuff.

Wow, awesome stuff here, Ray. Thanks! FWIW, I watch the Zwift stream on a giant smart HD TV. Looks pretty good to me but my computer Zwift riding resolution is low (ancient Win 8.1 PC), so my standards might be low…

Super interesting insight. Thanks for reporting on this. And interesting thought about offloading the GPU to a cloud service. Since the user already needs to have a computer/smartphone as the interface between the smart trainer and zwift, I’m not sure what would be gained unless we start seeing trainers that are cloud connected. And I think I answered my own question right there. Lol. Trainer companies, you can pay me later for that idea.

Okay, but what happens if T.A. Anderson decides to unplug from his pod in the NUC? :)

Super fascinating read, thanks Ray!

Great article! Almost as complicated as the real TdF broadcast. I’ve enjoyed watching the races. Any details on how they ensure proper trainer calibration, or are they just hoping for the best?

Thanks!

For the vTdF they’ve got some documents to help guide riders, but for the most part it’s seen more as a PR thing than a super competitive type thing. So some of the aspects that are there for other races with legit money on the line aren’t there for this.

Zwift has been going back and forth on whether to use power meters or trainers as the ‘correct’ known good source. Velonews actually had a great piece on it earlier this week. There’s pros and cons to it, but ultimately, the answer is one that hardware partners don’t want to people to hear: Some trainers are simply less accurate, and some power meters are simply less accurate. And potentially, not accurate enough.

How and when Zwift (and other platforms) figure out how to deliver that message to not just pros but consumers in races has been an industry discussion for years.

There’s accuracy issues, then issues on what’s being measured. I’m just having fun and challenging myself so am happy with my KICKR, but I’d think any serious racer would want a pedal or crank-based power meter, since it’s upstream of drivetrain losses.

Reality, of course, is it’s power at the rear wheel, not the crank, which propels the bike. So ideally everyone would be on smart trainers and use those as their power.

It gets complicated if trainer companies “calibrate” against an SRM, for example, in which case the trainer, despite being downstream, is emulating upstream. But I assume accuracy implies power measured at the point of measurement.

Another accuracy issue is weight scales. There was a study where the authors compared readings from a variety of publicly accessible scales in gyms, health clinics, etc, and the variation was close to +/- 1 kg. This is a huge source of variance compared to differences in fitness between close riders.

Oh yeah – there’s so many levels to this it’s nuts.

Like you said, there’s what riders want and what science says is better/more accurate.

Ultimately, I think what’ll happen is they’ll certify specific trainers for racing which are non-calibratable (akin to the Tacx NEO series), and which are ‘known good’ – at least in terms of consistency. Which, to be fair, is exactly what they said they’d do a year or two ago. Just hasn’t quite happened yet.

What prevents cheating by knocking 5-10 kg off one’s weight?

Nuttin’.

Awesome article Ray!

Merci beaucoup

candidate for your best blog post of the year. Thanks for it

Thanks! I like getting to geek out!

Oh yeah? Well I’m playing on an iPad Pro first generation with a busted battery so it’s got to be plugged in the whole time. Take *that* ZwiftHQ.

But ya know what? When you finally replace it, it’ll be the most liberating feeling ever to not be tethered to the wall anymore!

That’s a fascinating look at how they do this. But I was kind of wondering something else.

Namely, how did this all come about? When was the decision to go forward with this, and from a software development point of view, when were the parameters of the France world actually set down, and when were the parameters of the stages actually set down? Was some of this done ahead of time prior to Covid, or was this something they really only started after the live race was cancelled for the year?

And another little detail. I notice that it is never night in these races – they must have turned something off for the duration of the race? Even the 1st 2 stages in Watopia were never at night. So did they add a way to control the day length for certain events?

The Tour de France isn’t cancelled; it starts 29 August.

It is so stupid that powerups are used. Watched one of the women’s race an only those that had the one right powerups ended in top 10, rest had no changes in the sprint. It is like allowing virtual doping in the race, nothing to do with sport. Should be banned.

I watched stage 5 last night and the entire time I was thinking “how can they make this more interesting?” as I couldn’t watch for more than an hour before the novelty of the new scenery wore off.

Is Zwift’s end goal to make money from sponsored e-racing events or are these events just marketing to attract new paying zwifters?

I enjoyed the women’s race yesterday, mainly because there were a fair few of the top riders involved. In the case of the men’s there were a few “names” but they were often making up the numbers rather than competing.

Is a Zwift race ever anything but hanging on to the front group and sprinting at 4s out?

Also it’s good to know that there is a problem with the quality of the video feed. I spent ages yesterday thinking my Chromecast was on the blink ?

Great write up! I work for Simply NUC in the UK and I’m also a keen Zwifter, so combining the two has been a pleasure to read. I’ve been racing the Cycling Ireland league series with a number of racers doing their own live feed from home, which is complicated enough never mind the professional races being broadcast on Zwift. Good to see the Hades Canyon managing such complex programs. I look forward to more of your blog! Stephen